Participatory taxation

In 2024, former French Prime Minister Gabriel Attal proposed participatory taxation to enhance public trust and democratic engagement, but it faces criticism for potentially undermining fairness. While participatory budgeting has had success in promoting transparency, applying these principles to national taxation raises concerns about inequality and politicizing public funds.

Eliot Forterre

1/14/202510 min read

France and the case of participatory Taxation

On the 12th of August 2024, former French Prime Minister Garbiel Attal tried to introduce a new project of a “participatory tax system,” allowing taxpayers to determine the use of a percentage of their taxes. This project was supposed to be part of a broader framework, namely the “Action Pact for the French," aiming to build legislative compromises around six key issues:

1. Restoration of public accounts and strengthening of economic sovereignty

2. Defence of republican values, secularism, and institutional renewal

3. Improvement in purchasing power, housing, and working conditions of the French

4. Environmental Protection

5 . Strengthening security

6. Improvement of public services, particularly in the areas of education and health

The concept of participatory taxation is an “old liberal dream” to try and make people reconnect with democracy and “get what [they] pay for, ” as Attal said himself on the 25th of April 2023. At the time, this statement was made in the context of creating a new website named Enavoirpourmesimpots.gouv.fr where citizens could see how the state would spend their money. This is not the first time a participatory tax system has been mentioned in France. It appeared for the first time in 1789 with the Patriotic Contribution but failed. Hence, most political parties have argued against any form of participatory tax system. This global tendency has been eroding recently, with some parliamentarians advocating for more transparency, especially concerning taxation in an attempt to “conciliate people” (Le Monde, 2016) with taxes. A troubling timing to ask for more transparency in the French governmental system

The importance of taxes in democracies

A crucial question is whether tax systems are key democratic features. Does changing them improve democracy or solely people’s perception of democracy? A priori, taxes have been part of all political organisations for centuries.

In Ancient Athens, the “Eisphora” (war tax) was levied on the wealthiest citizens in times of war. This tax was imposed to fund military campaigns. Wealthy Athenian citizens were expected to perform liturgies, which were public services that involved funding important civic or military projects. These included financing a warship (trierarchy), sponsoring festivals, or supporting the construction of public buildings. This system placed a significant financial burden on the wealthiest citizens but was seen as a way to gain prestige and honour within the community.

Another prime example would be the Spartiate Property and Contributions. In Sparta, full citizenship came with the requirement to contribute to the common mess (the Syssitia). Spartiates were expected to contribute food and resources from their land to these communal meals. Failing to do so could result in the loss of citizenship rights. Economic contributions were, therefore, tied to communal participation and the maintenance of one’s status as a citizen. The first democratic systems, just like other political regimes, required financial participation, mostly from the wealthiest citizens. Just like then, financially participating in the community is crucial to show your involvement in it.

It is unsure whether taxes are a feature of democracies or political organizations. Even though the first forms of democracies already required financial participation, feudal and authoritarian systems also asked for various taxes. The key difference lies in the nature and use of these taxes. Democracies are accountable for their spending and the use of the money is decided by the citizens (even if it is indirectly), while other regimes are not accountable for their spending and are even less questioned on the nature of the taxes. One could argue that feudal systems had some sort of accountability where citizens had to pay taxes and lords had to protect them; Democracy turned this tacit procedure into formal accountability.

Acknowledging that taxes are not exclusive to democracies doesn’t mean that studying them is irrelevant. On the contrary, having shown that even in the early democracies, taxes had a predominant role, we can assume that they are a key driver of democracy, empowering people. We could therefore assume that more direct taxation systems and more participatory systems are more democratic and would ensure better public spending. Nonetheless, is it the case? Do we have evidence of this?

Participatory taxation and Participatory budget

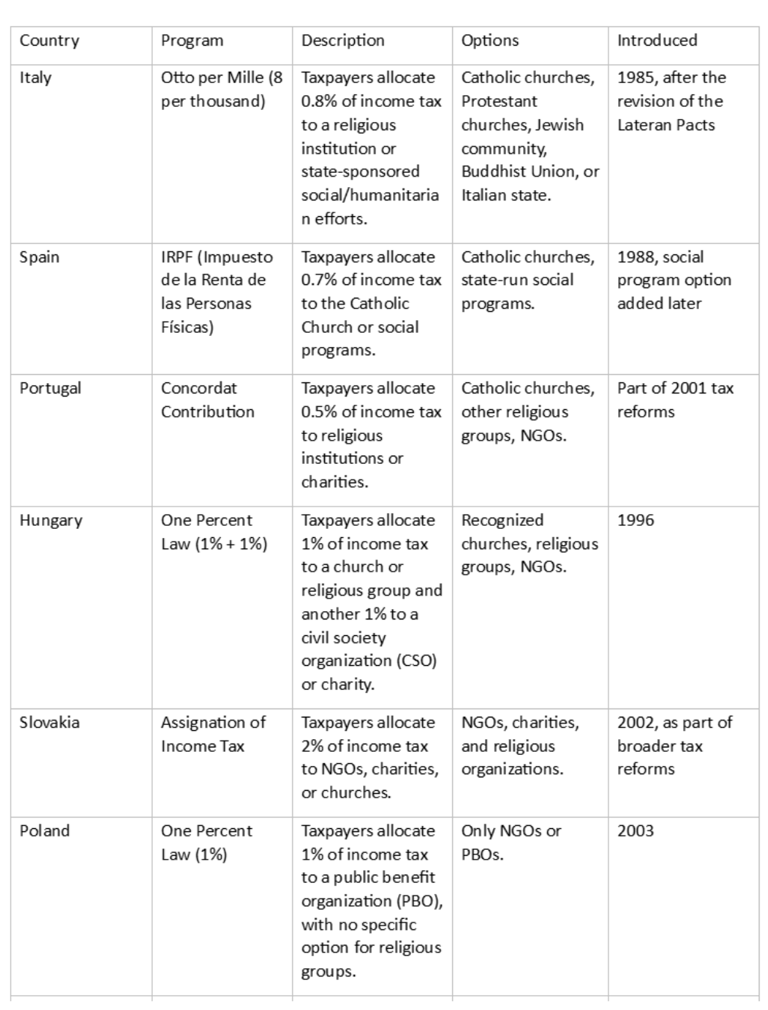

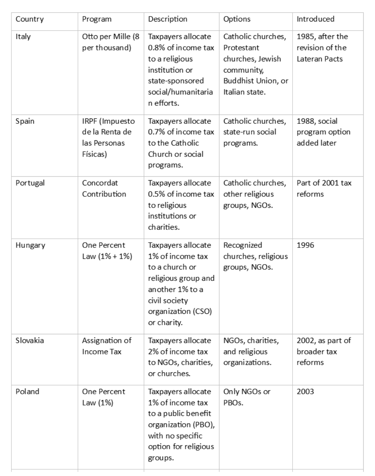

The legitimacy of participatory taxation systems in France has been criticized countless times by parliamentarians who described it as a “democratic masquerade," a “screen for inaction," a “public money fair” or even an “instrumentalization of citizens”(Le Monde, 2019). Nevertheless, some of its direct neighbors have already included similar systems, such as Italy with the Otto Per Mille since 1985.

For a long time, participatory taxation systems have existed through religion. Countless countries have decided to give citizens the choice to allocate a part of their taxes to either religious communities and/or a social cause. In Italy the Otto per miller (8 per thousand) allows citizens to allocate 0.8% of their taxes to a “recognized religious institution” or to state-sponsored social and humanitarian efforts. But with this, problems arise. The first problem is that these systems put in competition social causes with religious communities and that humans are more sensible to problems that directly relate to them. Secondly, the term “recognized” religious institution can be argued to be a cause of discrimination. In Italy, for instance, there is a possibility to distribute taxes to Catholic churches, Protestant churches, Jewish communities, Buddhist Unions, or the Italian state. Recently the case of including Jehovah’s Witnesses has been discussed in the Italian parliament but not yet ratified. On the other hand, the Muslim Church has not been considered while Italy holds 1.4 million Muslim citizens for 59,342 million inhabitants in 2024, according to the Worldometers, which represents 2.4% of the total population. The government justifies this as a precautionary measure tackling the lack of a central Muslim organization creating the fear of indirectly funding terrorist groups.

Many similar systems can be found all around the world, especially in Europe:

In trying to distinguish these different systems, here are 2 key distinctions:

Voluntary Allocation vs. Church Tax: Systems like Italy's Otto per Mille or Hungary's 1% Law allow voluntary allocation of taxes, while countries like Germany, Austria, and Finland use an automatic church tax.

Religious vs. Social Causes: Many systems support both religious and social causes, such as Spain and Hungary, where taxpayers can choose NGOs, charities, or welfare organizations

These systems aim to strengthen civil society and religious institutions by providing them with financial support that citizens directly influence. However, they typically cover a small portion of the total income tax. Religious participation remains an exception. It is very unlikely to see such a proposition make a breakthrough. There is not a widespread or established model specifically called "participatory tax system" in the way that participatory budgeting is recognized. However, there are examples of tax policies that involve consultation, input from citizens, or specific groups, such as:

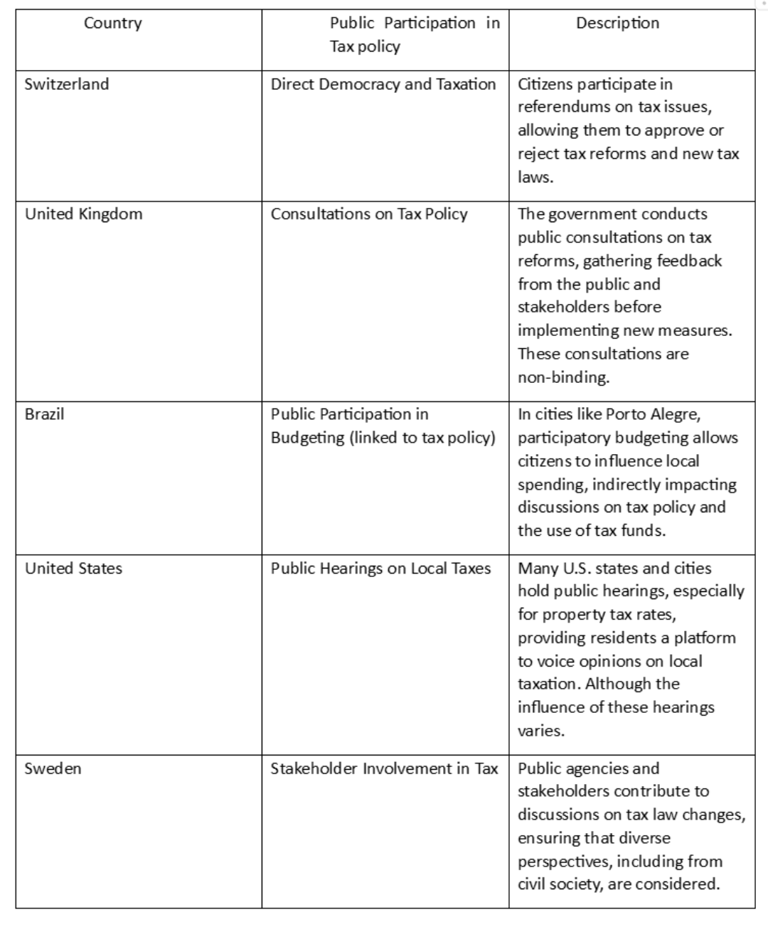

Public Consultations on Tax Policy: Some governments conduct public consultations or referendums on major tax reforms. For example, Switzerland occasionally holds referendums where citizens vote on tax issues.

Localized Input in Tax Collection: In certain regions, especially at local levels, residents may have input in how certain taxes are levied, such as through town halls or local boards.

Deliberative Democracy Models: Some experimental models of governance involve citizens' assemblies or panels that deliberate on tax policies and provide recommendations.

Nevertheless, realistically speaking, participatory tax systems, as opposed to participatory budgeting systems are much less commonly discussed in the academic and policy realms. Participatory budgeting involves citizens directly in decisions about government expenditures, whereas a participatory tax system would imply some level of citizen involvement in decisions about how taxes are structured or collected.

Participatory budgeting: a small-scale solution?

Participatory budgeting appeared in Brazil at more local scales and quickly spread around the world. Participatory budgeting would be a more local scale of participatory taxation where a part of citizens’ taxes is pooled to finance projects that are selected by citizens. Porto Alegre, in Brazil, created an institutional guide to participatory budgeting after the victory of the PT in 1988. The cabinet had realized that most of the money was being invested in the functioning of existing projects and not the creation of new projects. The PT transparently decided to state that it was lacking funds for the schools and decided to elaborate on funding, taking into account different economic situations. Therefore, in 1988 one of the first forms of participatory budget was born, named the “Orçamento Participativo." They reformed the municipal taxes based on local realities, making it more progressive on the estate and fixing higher rates for the inhabitants of richer districts while benefiting the poorer districts. At first, only 700 citizens participated, attaining 18,500 in 2002 and 15,000 in 2011.

Since 1988, participatory budgeting has experienced significant growth in the EU, becoming deeply integrated into various regions. It has been primarily developed as a tool to enhance democracy, foster participation and strengthen the relationship of trust between the public and institutions. In France, the 2002 law Vaillant created more and more district councils in cities gathering sometimes more than 80 0000 people. In the UK, 'community grant-making' is an alternative model involving small community or service funds allocated through an open call for proposals. These grants are typically for projects that address local needs, promote social cohesion, or support community-driven initiatives. The process is designed to be inclusive, allowing grassroots organizations and community members to have a direct role in shaping and benefiting from public or charitable funds.

We could summarize the positive impact of participatory budgeting in 9 points (Le Monde, 2016):

One of the only tools that allows citizens to have a say in the budget of local authorities.

Enables citizens to participate in decision-making processes (e.g., in Grenoble, an unhoused citizen named Apache proposed a project to create a space offering social and legal support for vulnerable people).

Opens voting rights to residents who don't have them but pay taxes (such as immigrants or young people under 18).

Provides direct decision-making power to citizens, not just participation.

Transforms the role of the administration, which uses its expertise to support citizens by providing cost estimates.

Encourages citizens’ imagination and creativity.

Leads to concrete projects.

Increases transparency.

Strengthens citizens' power to take action.

On the other side, several negative aspects have to be mentioned when talking about participatory budgeting.

According to the sociologist Yves Sintomer, participatory budgeting is suffering from the Jourdain Street paradox (Le Monde, 2016). It became a one-way street after a petition from citizens who thought the street had too much traffic. Consequently, the traffic moved to the street next to it. This led to a new petition for the street beside Jourdain Street. This example shows that local realities might be contradictory and that citizens might not have all the analytical tools to make the right decisions. The best way to illustrate this example in simple terms is a card on which it is written on one side “what is said on the other side of the card is true” and on the other side “what is written on the other side of the card is wrong." Local realities can be contradictory to the extent that solutions can’t be found without taking into account the big picture.

Another issue is that local representatives may use participatory budgeting to turn the investment budget they are given into a functioning budget. The example of Porto Alegre speaks for itself, as all the budget that was supposed to be invested in the development of new projects was used by politicians to maintain the quality of already existing infrastructure (the functioning budget). Politicians can cherry-pick the projects and manipulate them.

Finally, these systems can only work in digital democracies where citizens can vote online. This adds up to the fact that citizens may get tired of voting, or only specific profiles of people more politically aware and engaged would take the time to do it. The example of the US has shown us that intense political stimulation can hurt voter turnout.

Economic participation: A true democratic evolution?

In 1819, the Swiss political philosopher Benjamin Constant declared that direct democracy was the ideal democratic system, but due to the lack of education in societies, the implementation of representative systems was a necessity. Observing the growing democratic deficits in many countries, with parties and influential political figures advocating for the rule of law, wouldn’t it be the time to give back democracy to the citizens? Is participatory taxation a possible evolution for democracies, or should it stay local with participatory budgeting? Would parliaments be prepared to accept this kind of measure, which would render part of their job obsolete given that it is the parliament that votes on the budget?

These were the first considerations that came to my mind when I first heard about the implementation of participatory taxation on a national scale. Nevertheless, national participatory taxation systems do not seem to be the righteous path to better democracies. Acknowledging that total participatory taxation is an unrealistic and unsustainable endeavor, we can also fear that implementing participatory taxation on a small fraction of people’s taxes would have severe negative repercussions.

There is a strong possibility of a drift where the richest would finance the state through a convergence of interests. While voting has the advantage of being the most neutral and equitable means of political expression, participatory taxation gives citizens an unequal political weight as taxes are a percentage of citizens’ income.

Participatory taxation could also transform citizens into consumers of politics where their taxes become investments. States have logic of their own. As much as these systems may increase transparency and vertical accountability to prevent misuse of public money, the downside might be that citizens do not understand how their money is used. People may ask to reduce taxes as they are not satisfied with states’ actions. Furthermore, states’ financed projects need long-term, constant funding while people are too inconsistent to guarantee sustained funding. Finally, elites could manipulate public opinion in favor of “positive” actions, knowing that they will be chosen over the rest.

Participatory systems allowing to fund different matters than religions and social causes have not been tested at a national scale. Therefore, we can’t say that their effect would be counterproductive, solely that in theory there are some threats we should be aware of for better implementation in cases where taxes appeared to truly help democratization.

Participatory budgetting over space (Batocci et al., 2023, p. 764)

Eliot Forterre

Bartocci, L., Grossi, G., Mauro, S. G., & Ebdon, C. (2023). The journey of participatory budgeting: a systematic literature review and future research directions. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 89(3), 757-774.

Le Monde. (2016, 14 juillet). La démocratie autrement (1/6): Le budget participatif. LE Monde. https://www.lemonde.fr/festival/article/2016/07/14/la-democratie-autrement-1-6-le-budget participatif_4969435_4415198.html

Le Monde. (2019, 8 novembre). Rappelons les vertus politiques du budget participatif. Le Monde. https://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2019/11/08/rappelons-les-vertus-politiques-du-budget participatif_6018424_3232.html