Straggle Away From Snow, Berlin

Brody L.

4/22/202537 min read

To what extent can a travel blog document the truth of a journey? It has been three weeks since I came back from Berlin, through a chaotic rearrangement of train and bus. I see the inevitable gap there, that I had retreated back to my ordinary life with the lasting memory of Berlin. The magic is gone and I have to hurry up and solidify the remnant into words, not pictures. Sharing our moments on Instagram is a proclamation that we recognize others’ power to interpret our lives as they will. But solo travel rips this chronic exercise off you, forcing you to sit down and give an official memorandum of the past. It is not instant, but an honest review on your diary that you grasp from tripping through strangeness.

The fact that I do not speak a word of German nor do I possess a funny German last name, grants me the very privilege of a true traveler. Travel is not the practice of a predictable foreign routine, but a humble taste of messy fragments of others’ daily lives. A working-class Brit wearing a nón lá in Pattaya is not an unknown, as we know what his exotic routine is. A retired Chinese woman following a guided tour in Paris, as we know what her eye-opening routine is. And we also know the hotels they lived in belong to the same international group. Reporting on the German election? Man, I believe it is called an excuse not a routine. Therefore, I apologize for readers who expect to gain more entertaining or informative covers on the German election.

Of course, I did not actually say so last time when someone asked me why I went to Germany. Seriously, even the biggest poser would not give such a speech, unless it was Anthony Bourdain, after three shots of Moonshine, in some random jungle in the Philippines. Instead, I said, “Oh, it’s because it’s (Germany) exotic for me.” And I would smirk with an innocent look, observing the momentary confusion or discomfort over my friends’ faces. Well, it turns out to be the correct way to use “exotic”, an East Asian guy throwing himself to Berlin, which was a complete unknown to him.

Solo trips are usually the main source of old bed-time stories because of the absence of witnesses. The best of them is definitely Gulliver's Travels, if nannies find politicians unable to fall asleep. The traveller went with no company and only ought to bring themself back. Expecting no specific audience, the traveller can piece together the jigsaw as they want. O was not by their side, nor was P, nor was Q. No audience participated through in that journey, so no one could hold the writer accountable. The writer could say, “the world is my oyster”, or “the world is my pistachio”, or even “the world is my quagmire”. However, the words shall be built upon the honesty the writer has with themself, the initial “unknown”.

The 21st of February was in any sense a late winter, but as the S-Bahn carried me slowly from Brandenburg Airport toward the city, the first thing I saw was an accumulation of snow, pressed shallowly onto the farmland, with a few ducks waddling about on it. I hoped that I would have enough time to stomp the snow more firmly in all corners of Berlin before it melted away. The city walk started right after I had left my backpack in the hostel. As I walked along Friedrichstraße, pedestrians hurried past under a gray sky, while ubiquitous election advertisements hinted at impending change. It was calm at noon; not too cold to walk on the slightly frozen slick pavement. The city felt almost static here, its rhythm driven by the comings and goings of people.

Passing Checkpoint Charlie, I paused before a small section of the Berlin Wall remnants. Surrounding it were large backdrop panels depicting a brief history of the Cold War and photos of young victims shot by guards at the Berlin Wall.

In the early morning hours of August 15, 1961 in Berlin, the construction of the wall is in its third day. Konrad Schumann was 19 years old and one of the many soldiers tasked with defending the long, rapidly growing wall, from Leutewitz, part of East Germany. The tides of history were destined to change his life profoundly; he was three years old when Hitler committed suicide, and when he was four years old, Churchill gave that famous Iron Curtain speech – the world divided in two, with both sides claiming to be the defender of freedom.

“Come here, come here!” The people over there kept shouting. The fence had been built to the last part, and it had not yet become a two-meter-high concrete wall with barbed wire stretched over the top, but merely a barricade. Perhaps Schumann himself couldn't say what he was feeling inside at the time; his great leap over the thistles shocked everyone, and the photographer Peter Leibing, who happened to be there, captured the moment – an East German soldier wearing a helmet flew over the fence. That early morning moment became one of the most memorable images of the 20th century, and in the height of the Cold War it was interpreted as a “flight to freedom”.

The fate of the man in question is not like a photograph that can't be framed in its brightest moment. Konrad Schumann was picked up by a West German police car on standby and subsequently granted the right to live freely in West Germany. He settled in Bavaria, West Germany, and met his later wife in the small town of Günzburg.

But the shadow of the Berlin Wall did not disappear inside him. In the years that followed, Schumann must have continued to hear of many escapees like him, but most met an ill fate. They were stopped by the police, shot at, and knocked down by electric fences… The Berlin Wall has been raised from its original height of 2 meters to 3 meters, and the searchlights on the towers shine extra brightly at night. He must also have feared for his family and friends still in East Germany, who had no idea what would befall them due to his recklessness.

“Only after November 9, 1989 (when the Berlin Wall was dismantled) did I feel truly free.” Schumann said later. But even so, he rarely visited his parents and siblings, as if Bavaria was his true home more than his birthplace. Depression also plagued him, and on June 20, 1998, he hanged himself.

Most tourists appeared somewhat somber as they lingered moving slowly whilst taking pictures. Behind me was a group of excited young Brits; one wearing shorts animatedly recounted a recent football match held in Germany. Nearby was an inexpensive fast-food joint catering to tourists, selling fries and waffles while energetic beats from the kitchen played Say You Will Never by Lian Ross.

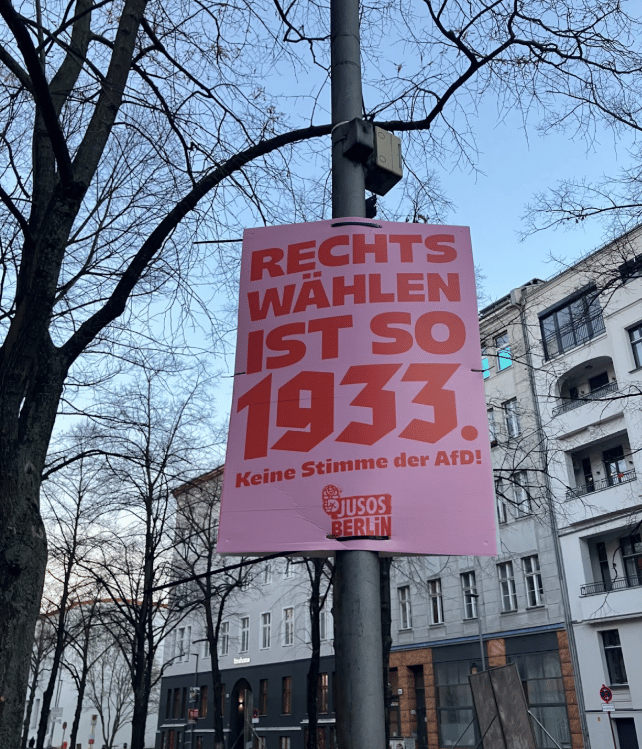

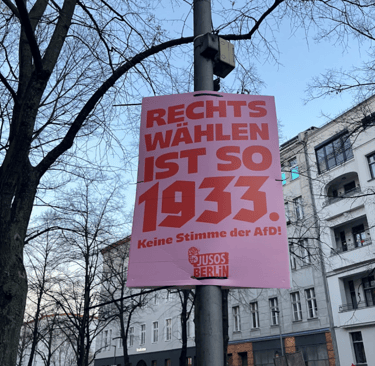

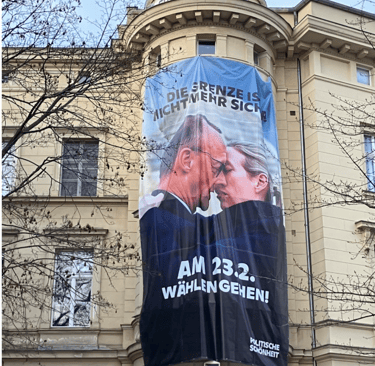

Continuing on my way, I noticed repeated faces of politicians; one poster featuring Merz had been defaced with “FCK NZS.” Politicians from CDU, SPD, and FDP stared back at me in a row while Scholz smiled from further away; I was not sure if I, or anyone would feel comfortable with those gazes as I stepped over melting snow, crunching beneath my feet.

As I walked past the Brandenburg Gate, a lighthearted atmosphere returned to people once again. Families held and hugged each other, and a group of girls roamed around, trying to find a perfect background for their bestie videos. Suddenly, a police armored vehicle blared the opening of Justin Bieber's Baby, deafening like a siren. The officers inside looked embarrassed and quickly turned it off, while their colleagues outside erupted in laughter. I entered the subway, taking the U5 line and getting off at Rotes Rathaus, right beneath the Berlin TV Tower, where a protest against budget cuts in higher education led by BSW was underway.

A friend of mine studying in Berlin showed me an email from her student organization that read: “Around a third of the financial means for the student organization were already cut for the year 2025. Necessary renovations for student housing or the funding for new, desperately needed housing were seemingly impossible with these cuts. Additionally, things like free canteen food or consultations with experts were in danger, as there is not enough funding for them.” The email ended with a political warning: “...the dismantling of the welfare state and the deterioration of living conditions is the breeding ground of extremist parties, thus further strengthening the AfD.”

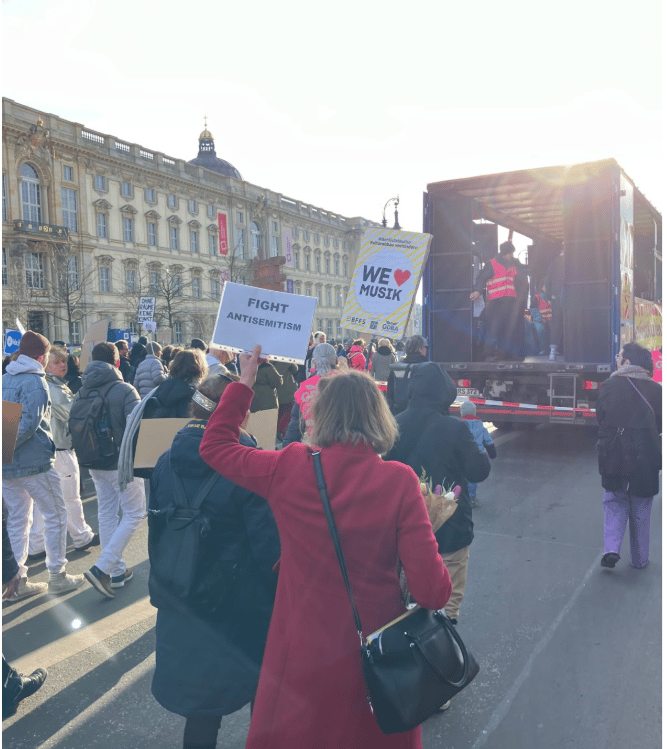

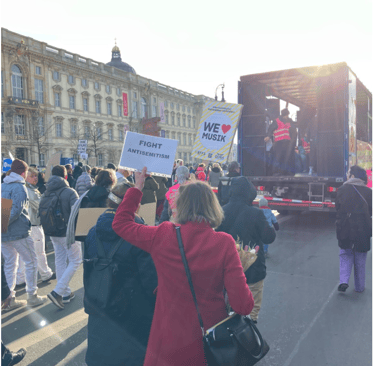

When I got out of the subway, all I could see was a sea of people. BSW and its supporters occupied Karl-Liebknecht Street entirely. At the front, a truck converted into a stage equipped with loudspeakers, where protest leaders delivered impassioned speeches that constantly prompted cheers and sharp whistles from the crowd.

A woman in her fifties said earnestly, “Vote for smaller parties; we shouldn’t let big parties dominate parliament. We should use diplomacy instead of military aid to end the war in Ukraine.” A woman held up a placard while looking after children. Two little girls approached her asking for snack pretzels. She said, “This budget cut affects not only education but also art funding. Berlin is an art city, but…” She glanced at a little boy playing by the fountain before continuing, “Sorry, my English isn’t very good. This is my child.” I asked her if she felt optimistic about tomorrow's election. After looking at her son again, she shook her head with a smile and replied, “No.”

On the other side, beneath the dry Neptune Fountain, students wearing keffiyeh from the Palestine Solidarity Movement held banners and chanted "Free Free Palestine," joined by a few environmental activists and young communists waving their flags. A handful of police officers stood by, watching idly.

A woman in a red coat held a bouquet and a sign reading "Stop Antisemitism". At first, she was hesitant to speak with me, repeatedly stating, “I am a liberal.” Following her gaze, I noticed my hands were full of communist newspapers, flyers, and pamphlets. I explained that these were given to me by those communists. She then said, “German schools teach about the Holocaust as mere history while ignoring the reality of antisemitism. October 7th was absolutely wrong, yet antisemitism is increasing.” She pointed to a photo of a baby and said softly, “You know, she is also German. And she’s dead.” Her eyes glistened with unshed tears. This woman was no stranger to these protests: Her name is Karoline Preisler, she is a member of the FDP. She is a somewhat controversial figure, and I guess the rest is for you to judge.

Berlin’s nightlife culture is considered the best in the world – a view almost universally accepted. I told you, reporting on the German election was almost an excuse. In 2021, German federal parliament voted to classify its clubs as "cultural institutions". It sounds absurd, doesn’t it? For the Senate of Berlin, since four years ago, there is no difference between nightclubs, opera houses, and classical concert halls; all are protected and supported by a lower tax rate.

The rise of nightclubs – brimming with drugs, electronic music, and carnal passion – is the offspring of a counterculture movement. In the 1960s and ’70s, counterculture was everywhere in the West. Yet the bitter irony of every counterculture is that if it becomes too successful – if it truly mirrors society’s underlying sentiments – it risks evolving into the very mainstream it once rebelled against. In Berlin, that mainstream is precisely the counterculture itself.

At the heart of it all lay self-loathing and collective guilt. In post-war Germany, one of the most crucial social processes was denazification. Roughly eight million Germans – about ten percent of the population – had been Nazi Party members. But serving the Nazi state wasn’t merely the duty of party members; it also came from a vast majority. The German Labor Front boasted 32 million members. Naturally, after Germany’s defeat, denazification became an enduring, monumental task. Many Nazi leaders and key figures were convicted – and even executed – in trials at Nuremberg and elsewhere. Those war criminals were found guilty. But what about the tens of millions of “ordinary people”?

If you grew up in 1960s or ’70s West Germany in an ordinary family, you couldn’t help but know that your parents, neighbors, even teachers, might – and very likely did – belong to the Nazi Party. Your Chancellor Kiesinger, your mayor, your judges, and police had all participated in the Nazi regime, committing unspeakable evils in the name of fanaticism and loyalty. As their descendant, you were burdened with guilt; history weighed heavily upon your shoulders, as though you were destined to atone. And yet, you had committed no crime yourself – you were probably even a good Christian. In this paradox, the society you grew up in appeared to have returned to normalcy.

Nonetheless, the NS era was over. Germany had paid a heavy price – reduced to rubble by bombings and then slowly rebuilt under the eye of occupants. No one can live forever in such deep-seated guilt, nor in the blaze of anger. To dwell in these emotions is to tear one’s life apart. Thus, the dilemma confronting the Germans was this: after committing such unforgivable crimes, they had to try to return to normalcy – even if normalcy meant becoming numb and callous, discussing mundane middle-class matters like going to work, clocking out, and spending weekends kicking a soccer ball with the kids. By the 1960s, West German youth were asking their parents: “What exactly did you all do back then?”

But the tension, reflection, and activism of the 1960s and ’70s were not unique to German youth. Across the West, young people felt a shared malaise – a deep disenchantment with modernity and capitalism. In France, student uprisings in May brought down de Gaulle; in the United States, protests against the Vietnam War, the rise of hippies, and rampant racial strife reshaped society. Yet while French and American youth traded their suits for jeans and marched on the streets – sometimes waving Mao’s Little Red Book and dreaming of a Cultural Revolution – the intellectual cost of ignoring the darker consequences of China’s communist experiment (its conflicts, famines, executions, and moral decay) was high.

German youth, having only just emerged from the horrors of Nazism – witnessing firsthand the devastation wrought by a colossal state machine and collective hysteria – and living so close to East Germany under communist rule, found themselves unable to romanticize communist promises.

Instead, they embraced another radical left-wing impulse – the anarcho-left – an extreme rejection of capitalism and modernity that would eventually give birth to militant Red Army groups. This very ethos laid the political foundation for West Germany’s electronic music and nightclub culture. However, didn’t the Nazi regime also criticize the decay of modern civilization? Their solution was to retreat to the past, pledging to resurrect a once-great classical German spirit. In contrast, the anarchists didn’t try to turn back time – they opted for an avant-garde, revolutionary route. One of their bold experiments was electronic music, an entirely new genre that refused to kneel to Anglo-American pop music, severing, betraying, and even deliberately subverting the venerable German classical music legacy.

Take Kraftwerk, the pioneers of German electronic music – sometimes hailed as the most influential band in Western pop music outside of The Beatles. Their name might seem modest in light of such praise, yet without them, popular music over the past 45 years would be unrecognizable. Just 45 years ago, nearly every mainstream pop band relied on traditional instruments – (electric) guitars, bass, drums – even when they employed electronic instruments merely as keyboards. But when Kraftwerk burst onto the scene in 1970, their music, created entirely from electronic devices, stunned everyone. We stood impassively behind those cold machines, yet felt our bodies compelled to move as if possessed.

At the same time, thanks to West Berlin’s anarchic atmosphere, squatters began occupying abandoned industrial complexes. With minimal police interference, parties grew longer and more uninhibited, gradually evolving into the precursors of today’s famed nightclubs. Berghain, for example, was born many years later in an abandoned power plant.

The signature 4/4 beat of house and techno music is intertwined with this industrial spirit. Within those cavernous, derelict spaces, people found themselves moving in mechanical unison – never stopping, like machines until all energy was spent. Each person became a tiny cog in a vast automated machine, shedding human inhibitions and societal constraints.

My friend was clearly not impressed by this historical pontificating. “After all these years, Berghain is just a place to dance,” she snapped. “Do you really think the people inside are still that rebellious?”

She hailed from a small Bavarian town not far from the Czech border, and only arrived in Berlin at the age of twenty. I asked her what to wear to get into Berghain. “Americans go to clubs with fake lashes, high heels, and tight dresses – showing off every curve. That’s faking. Okay. We wear leather, all black, probably Adidas sneakers – we fake rebellion, faking poor.”

I didn’t argue. I mean, she is a Bavarian. When in Rome, be Roman. I donned a black leather jacket and made my way into Berghain – dancing until dawn broke at six in the morning. I wiped the memory inside off my mind the same way they put a sticker on my phone camera lens.

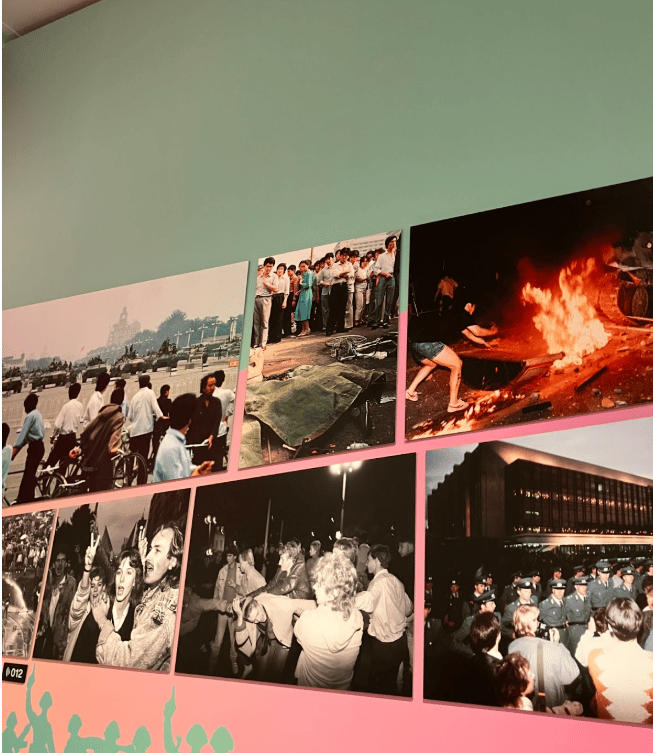

Everything I expected to see was there. The surging crowds beneath Tiananmen, burning bicycles, body parts, couples hiding under bridges from the army, and the lone man standing defiantly before three tanks. I didn’t bother reading the descriptive plaques – I knew all of this by heart, too long ago. And yet, my tears still came. I had once thought I was beyond crying over this.

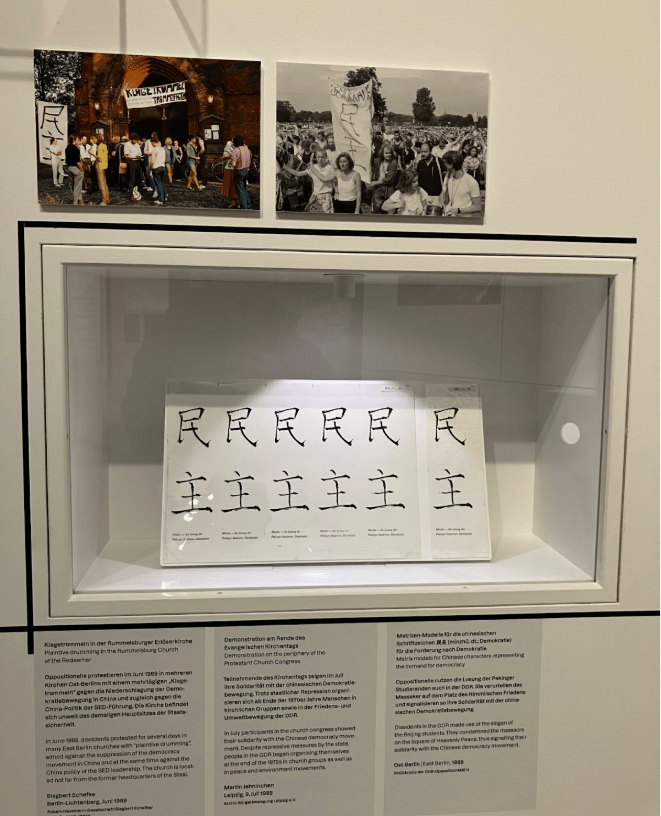

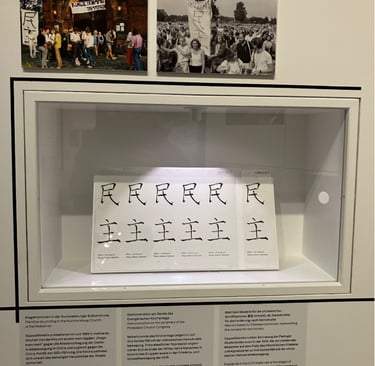

In 1989, Leipzig, September 4th, the Monday Demonstrations erupted. The East German government considered deploying the military for a crackdown. Protests of various sizes swept across East German cities. On November 9th, the Berlin Wall fell. Earlier that same year, in April, university students and workers began gathering in Tiananmen Square, protesting against corruption, demanding accountability for the Cultural Revolution and the Great Leap Forward, and calling for democracy. In Beijing alone, anywhere from 1.2 to 3 million people took to the streets, and protests broke out in over 400 cities nationwide. Deng Xiaoping eventually ordered the military to intervene. On the night of June 3rd, troops entered Tiananmen, and the crackdown continued until the following morning. The death toll remains uncertain to this day, ranging from hundreds to tens of thousands. No open investigation, no accountability, no visibility to this day in China. Tanks and machine guns were used against unarmed civilians. The hope for peaceful democratization in China was shattered. Many Western nations imposed economic sanctions, and the arms embargo on China remains in place to this day. East Germany’s SED expressed support for the Chinese Communist Party’s actions.

The Chinese Communist Party’s bloody massacre of students and civilians caused panic in East Germany, where it was referred to as the "Chinese Solution." But the spirit of the Chinese students inspired the East Germans, and the West’s tough stance toward China also discouraged the East German government from deploying its military. To this day, you can find photographs in historical archives of East Germans in 1989 waving Chinese-character banners that read: “民主 (democracy).” In the West, many still know little about the Tiananmen Massacre, let alone its connection to the fall of the Berlin Wall. The German Historical Museum was telling "the story of the unknown others." The sense of loss I had felt at the DDR Museum finally melted away here.

Few months ago, I read The Museum of Unconditional Surrender. Another memoir-like book from Dubravka Ugrešić. The same dream-mumbling, the same diaspora. Many story-tellings began with a photograph. And I simply could not express it better, so I humbly quote below:

“There is a story told about the war criminal Ratko Mladic, who spent months shelling Sarajevo from the surrounding hills. Once he noticed an acquaintance's house in the next target. The general telephoned his acquaintance and informed him that he was giving him five minutes to collect his 'albums', because he had decided to blow the house up. When he said 'albums ', the murderer meant the albums of family photographs. The general, who had been destroying the city for months, knew precisely how to annihilate memory. That is why he 'generously' bestowed on his acquaintance life with the right to remembrance. Bare life and a few family photographs.

“Refugees are divided into two categories: those who have photographs and those who have none,” said a Bosnian, a refugee.

At another Saturday flea market, I saw a lot more photo albums, which I don't see often at flea markets elsewhere. Berlin seems to be more obsessed with second hand, with passing on items, than any other place in the world. Sexy or not, being poor is one thing, yet things live longer than people. Photo albums live longer than their owners. There are many long lives hidden in an old coat, which has meant something to someone and will mean something else to someone else. This is how the soul migrates.

A morbid obsession, or more like mourning; and the flea markets are hearths in this sense for past souls. Berlin is a city of museums, a city of ruins, a city of memories where ghosts float under the grayish-blue sky. Berlin is liberated, yet never free from one bit of its past. Schizophrenic.

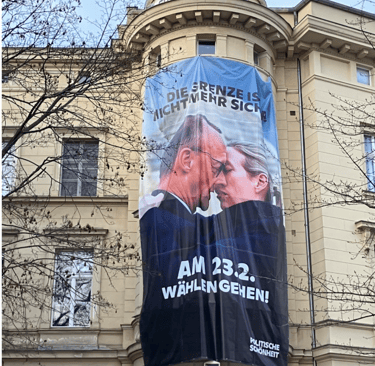

Aimlessly, I walked toward the German Historical Museum. Frankly speaking, I was drawn in by the giant protest poster hanging outside – one depicting AfD leader Weidel and CDU leader Merz locked in a wet French kiss. The theme of the exhibition was "Roads Not Taken: From 1848 to 1989." 1989, 1989, 1989 – those four numbers flashed repeatedly in my mind. My heartbeat quickened, the numbers echoing silently as I murmured them to myself. Without much pause, I breezed past the nearly empty 1848 hall, bypassed the elderly couple absorbed in the 1914 exhibit, and walked past a group of high school students listening to their teacher explain the 1936 occupation of the Rhineland. I headed straight for the 1989 hall.

After the reunification, the Berlin government was heavily in debt due to the huge costs of reconstruction. At its wit's end, the Berlin government turned to the federal government for financial support, but was ruthlessly rejected. In a fit of rage, the Berlin government decided to sue the federal government, but still lost the case.

When the Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) judge declared the defeat of the Berlin government, he quoted this phrase, “Berlin ist arm, aber sexy”. The next day this ironic phrase “poor but sexy” quickly hit the headlines, and eventually became the international symbol of Berlin.

Yet, this free spirit of comfortably being poor but sexy has to be traced back to the chaotic time of reunification, echoing Jan’s short city history lesson. In 1990, with a significant migration movement, about 25,000 old apartments in the inner city of East Berlin were vacant, while a large number of houses built under the East German housing program were also vacant.

From December 1989 to April 1990, there were about 70 squatting cases in East Berlin. In contrast to the “illegal occupancy” status of the West Berlin squatting, the East Berlin squatting were open and decisive. Anarchists put up banners, closed windows, and even set up barricades, making the occupied houses a testing ground for libertarians.

Initially, the squatters of East Berlin were mainly young East Germans who knew each other well from subcultural and political activities. Soon the squatting movement attracted a flood of young artists from West Germany and even from abroad. The large number of unfinished and unoccupied buildings allowed young people to settle down in Berlin for very little money, and allowed artists to be as creative as they wanted without having to worry too much about making a living. The main function of the squatted houses in East Berlin during this period was to create space for the “self-realization” of the squatters. This was followed by citizen activism groups, whose demand was to prevent the complete demolition of the old settlements in Prenzlauer Berg and Mitte. The demand was quickly answered and the old neighborhoods were legally preserved and financed for renovation.

Mainzer Straße was typical, with more than 10 buildings squatted. In addition to setting up amenities such as a bookstore and a communal kitchen, the squatters also established the first Tunten (gay) housing project and lesbian housing in East Berlin here. At this time, squatting became a practice of confrontation with the authorities and a symbol of self- political orientation.

After a series of violent clashes with the police in 1990, most of the squatters had to come to negotiation. Most of the squatted houses are used under contract after signing a use agreement with the Housing Council. According to the statistics, 30 occupied houses were evicted and the use of 90 occupied houses was legalized. Inspired by the squatting movement in East Berlin in the 1990s, the Senate of Berlin continued to invest 250 million euros in the 1990s in a “self-help housing policy” program. A total of 3,000 housing units were renovated under this program, including former squatted houses.

As a not-so-typical German city, Berlin is cool, at least no one would doubt that. However, 22 years later, is it still poor and sexy?

I followed the procession while conducting interviews until we reached Berlin Cathedral. Suddenly, from the front truck came singing.

“Diese Stadt Gehört uns allen

Kultur darf nicht gestrichen fallen

Wir sind laut (wir sind laut)

Und richtig so (und richtig so)

Berlin ist Kunst (Berlin ist Kunst)

Kultur let’s go (Kultur let’s go)

Wir sind laut (wir sind laut)

Uns richtig so (und richtig so)

Berlin ist Kunst (Berlin ist Kunst)

Kultur let’s go (Kultur let’s go)

The singer then announced, “I am also an immigrant. I came to Berlin 15 years ago. Then I learned German. I am so proud to be a Berliner! There are many people here – especially migrants – who don’t have voting rights. So please use your vote tomorrow and think about those who don’t have it. And don’t ever give up on your dreams! I’ve come a long way to be a singer; besides that, I’m also a comedian, an activist, queer – a drag queen – and yes, I’m also Jewish. Here in Berlin.” The whole march laughed. The singer was quite sexy, that was true.

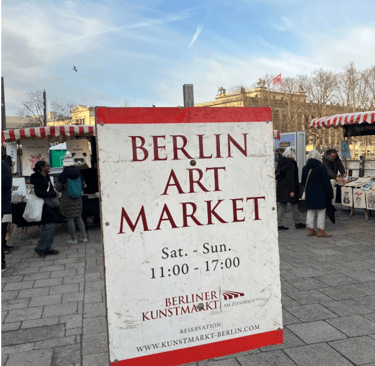

As we passed the Altes Museum, I pulled out a flyer from a communist organization inviting me to a seminar at six o'clock. I thought, I knew where I would head tonight. Before that, I decided to take the long way around. Just under the Berlin Cathedral, the Berlin Art Market was packed with people, and protesters went on a separate way. I walked through it fast, faster when I saw the price tags of those delicate toys, fine-lined paintings and so many souvenirs. But ultimately, about one-fourth to the end, I stopped at a tiny stance. An old man in a navy blue, sort of worn out jacket, burying his face into a book, was clearly minding his own business. Reading was probably more of a business for him. Stacks of old maps, stamps and some rough pencil drawings were piled up, in a tidy manner. So I guess he did not sell it well. On the edge, some photograph albums caught my attention. I looked through, and I saw boys, girls, mothers, fathers, a middle-aged man with a scar on his left cheek, and a few cats and dogs. You could tell they were beloved by their owners. Most of them were in black and white. They used to belong to someone, some families, but now they were here. They were public memories now.

I mean, sure, I walked around Berlin with a journalistic eagerness, hoping to create an exciting, or even a controversial story out of fling conversations, once-in-a-lifetime encounters and some wit use of her historical wounds. Yet, it is not how stories should be told.

Words do not mean anything, but stories transcend time, as they build a bridge between us and others’ lives. I hope at the end of this article, you enjoyed more stories than judgments. I see this clearer after I went back to The Hague, where I attempted to wake up on time, do healthier grocery and communicate with tax authorities. The avidness for a kitsch portrait of Berlin gets worn out, and the self-scrutinising pen gets handy. It is “life” that my pages should be about. The life we lived, the life we could have lived and the life others once lived but not much known.

Another protester, Jan, who had a disabled left eye, remarked passionately, “I’m not talking about millionaires but billionaires. Berlin is indeed poor; it’s outrageous not to tax billionaires here. Berlin’s strong leftist identity comes from being repeatedly liberated – East Berlin has long-standing communist legacies while West Berlin was once a refuge for men avoiding military draft in West Germany. Although right-wing parties have exploited communist history, leftist organizations that lacked parliamentary support in the 90s, have been deeply rooted in communities, establishing numerous cooperative housing and art projects. It’s unacceptable to witness decades of practice facing existential threats.”

Not far from Jan, there was a guy holding a placard that read, “ARM ABER SEXY DUMB”. Sure, anyone who has spent time in Berlin, whether a decade-long veteran or a fleeting tourist, is familiar with the phrase “Berlin, poor but sexy” – a slogan first attributed to former Berlin mayor Klaus Wowereit - but it was a scandal that really made it stick in the public's mind.

I sat alone on a bench outside the museum for a long time. The roads not taken, but the road we could have taken.

I walked quite a distance through commercial areas and somewhat dilapidated neighborhoods until I reached a community center near Kottbusser Tor. Through the glass doors, I saw several people seated at tables preparing to start; about twenty chairs were set up but only half were filled. The interior reminded me of an emptied bookstore. With the help of an interpreter, Leo, a man with a fine mustache, I managed to follow the discussion. The topics revolved around anti-right-wing movements, anti-racism efforts, and issues like Palestine – repetitive themes that finally left me drowsy.

The room was filled with young faces eager to engage in debate, and a few elderly who clearly caused troubles decades ago. One speaker began by addressing migration policies: "We need to focus on systemic racism and the shift to the right wing with parties like AfD." Another participant chimed in about how 15% of Germany's population lacks voting rights. A passionate voice rose from the crowd: "All refugees in Germany have a right to be heard.” Another respondent shared personal experiences of dehumanization not only against Palestinians but also those involved in solidarity efforts. They noted how even at anti-AfD demonstrations, Palestinian elements were unwelcome – a stark contrast they found disturbingly similar between both political sides.

Suddenly, loud noises pierced through as a loud group of demonstrators marched down the street – almost all dressed in black and many wearing masks. They were followed closely by several police cars and even a SWAT vehicle. Everyone’s face seemed mysterious in short breaks of shadow, then revealed emotion, lightened up by flashing red and blue lights; countless officers silently trailed behind them – perhaps forty or fifty in total. It took three or four minutes for the entire procession to pass by completely. Someone said “Red Army Faction.” The dull seminar finally dissolved under this excitement as half of the attendees rushed outside to see what was happening – I was no exception.

With questions swirling in my mind, I approached Leo who was smoking outside and thanked him for translating the seminar for two hours straight; honestly, I wanted to tell him it wasn’t worth it. He said he was happy to help.

Bewildered, I asked him how it could be the RAF if the third generation had already been gone for over thirty years. He explained the protesters were more like RAF sympathisers but indeed protesting for a member of the third generation – Daniela Klette, a suspected former terrorist. She was arrested a year ago after going on the run and living under a different identity for thirty years. And she lived nearby. Leo continued, explaining that a podcast hosted by a journalist identified her through an AI software, resulting in her arrest. Leo was obviously very concerned about the use of AI and privacy. After thanking him again I followed after the RAF marchers.

Before long, I spotted the demonstration from afar. The police seemed unfazed from behind; they marched silently and orderly as if attending an unwanted ceremonial training. I crossed over the police, hoping to ask some questions. But three people in a row all refused without exception – either turning away or giving me wary looks.

I noticed an alone man at the back of the demonstration who appeared relaxed despite being only five or six meters away from watching police officers; I approached him.

“Hey, I am doing a bit of journalism here…”, I said, attempting to gather more information. The man responded, explaining that he too had just stumbled into the demonstration. I proceeded to ask him why people were so reluctant to talk to me, to which he answered: “They are leftists. And journalists are not their best friends.”

The idea that “seeing a bigger world” through news writing has become obsolete for us, because the world keeps moving forward while we are trapped by the unspeakable. News, with its twenty daily updates, the buzzing at one in the morning, lengthy economic analyses, the sparse words of interviewees, and decisive moment photographs, can no longer change anything. Instant news here has helped no one; it brings overwhelming attention and trouble to the interviewees who were once hidden, only for readers to leave like the wind, leaving people in the news to struggle with more difficulties. For readers, it offers more of a sensational experience, a pastime for intellectuals and cynical students. Yet, I believe non-fiction has value, just as in-depth investigations, fieldwork, and ethnography do. I think that “documenting” itself has power and can change things; more romantically, I believe that recording the lives of 'the unknown' is valuable. As Foucault has said, they represent the fractured parts of grand narratives, where genuine “events” occur. It is precisely that, an unknown writing on the genuine events, past or present, for other unknowns, makes a travel literature readable.

Being the only person willing to talk, I decided to ask him about Daniela Klette. He explained that she had been held by police for a year now and despite being a suspected terrorist, was not charged with terrorism. Instead, they were charging her with attempted murder and armed robbery, framing her as a criminal rather than a political prisoner. Then he commented, “Well, here is how I think of it: she needed to get some money for her organization, right?”

Having shaken his hand, I moved toward the front of the crowd but faced more refusals. Until my gaze met that of an older man with gray hair, who gave out calmness coming with age. He had likely witnessed many upheavals throughout his life – threatened others and been threatened himself – and probably no longer took a stranger as a threat.

What was to worry about chatting with some curious young person anyway?

I mentioned the heavy police presence at the demonstration. Nodding, the old man pointed out the issue of police violence – or as he liked to call it “state violence’”. “You know Francesca Albanese?” he asked. But before he could finish, a female police officer urged us to walk faster. Quickening our pace he continued, declaring his frustrations with the silencing of Franscesca Albanese, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Occupied Palestinian Territories, by the German police. Calling the government hypocritical, he explained they call what happened in Ukraine a genocide but suppressed similar comments about Palestine. The conversation diverged toward military expansion, which the old man considered connected to the selective recognition of genocide. Though aware of Germany’s condemnation of Russia’s actions in Ukraine, he believed this stance was also about justifying its own military interests. Referencing the expansion of the military in the 1930s, he warns that this is not the first time.

He leaned over, and looked at me very seriously. “Look, I am 67 year-old and I have witnessed the world on the edge of a nuclear war, four times. Now we are forgetting the lesson we learned from the Cold War. We’ve forgotten.”

My third day in Berlin started in the early morning, very early. I watched as the orange sunlight slowly soaked into the blue canvas of the sky. The streetlights hadn’t gone out, and the office buildings in the distance were already aglow. A rat scurried past me, slipping through the iron fence and vanishing into the grass. Still, Berghain’s debauchery within dancing raged on, expected to last until the early hours of Monday, but I was on my way out. Some asked me how I got into Berghain alone, twice. And assumed it must be me wearing all black. Well, that was true but not necessarily the reason: A girl inside wore a gorgeous wedding dress and her move was so wild as if the venue was only hers. See, last night when I went to Berghain, I said to the bouncer, “I was there yesterday.” And I said the same thing to the bouncer the night before. I guess telling half of the truth does make you seem more mysterious.

A group of young British men, drunk and carefree, spilled onto the subway, blasting Careless Whisper. I could barely understand what they were saying or even singing. A girl nearby rolled her eyes, her bleached eyebrows creasing ever so slightly as she pursed her mouth. The passengers all wore the same expression, a kind of practiced indifference. On Berlin’s subway in the early morning, the commuters didn’t seem any more exhausted than the travelers at one-thirty in the morning for parties. Or maybe they were all the same breed – people who treated sleep as something to be scheduled at will. A woman selling newspapers shuffled by, her voice hoarse as she delivered a long, tired pitch that no one acknowledged. She lugged a massive backpack, heading straight for the next carriage. When I looked up again, the only trace of her was the glittering, fuzzy socks she wore, still sparkling as she moved away. And then I saw my station, Hallesches Tor. I pushed past the British guys, hit the door button, and darted out. Two of them, so drunk, nearly dropped their beer bottles, but instinctively said, “Sorry.” Polite and clear. Off the subway, a group of gorgeous Spanish men and women stood smoking and chatting.

Suddenly, a sharp panic struck me: If I don’t learn another language, I’d be doomed to keep the company of the Brits wherever I go on European soil. Lost in thought, I made up my mind to go meet some AfD supporters.

AfD's headquarters wasn't far from my hostel, and I caught a bus, not really knowing if the metro ticket I'd bought included the bus, but in any case it was a sparse, wobbly, ten minute ride. Jutting pink pipes were placed in the middle of the road as some kind of street art, and across the street was AfD's headquarters. This was a modern, multi-story office building with a minimalist design. The facade features horizontal bands of white plaster alternating with dark, tinted glass windows fitted with blinds for shading and privacy. I wasn't really expecting the headquarters of the party hated by Berliners to be packed with raging supporters, but I wasn't anticipating this kind of serenity. I forgot that nothing is open on Sundays in Germany. A mother, pushing a baby stroller, passed by carelessly, as if she were passing an automatic laundry. I think it's classic German humor, don't you?

So I moved forward, without a plan. On the way, I saw a small memorial, surrounded by flowers. I looked it up and found out that the triangle-shaped inscription, called Rosa Winkel, was a symbol that homosexuals were forced to wear in concentration camps during the NS era – the Nazi regime considered homosexuality to be a form of “anti-social behavior” that violated nationalism and reproductive policy, and therefore suppressed the homosexual community by law, imprisonment, castration, and massacre. After 1980, the pink triangle (Rosa Winkel) began to be reclaimed by the LGBT community as an anti-discrimination symbol.

The inscription carved on this triangle tablet reads:

TOTGESCHLAGEN

TOTGESCHWIEGEN

DEN

HOMOSEXUELLEN OPFERN

DES

NATIONALSOZIALISMUS

“Beaten to death, forgotten in silence.

Dedicated to the homosexual victims under National Socialism.”

If you're traveling in Germany, you'll see this triangular monument in many places – Hamburg, Munich, Frankfurt, even in Austria. But the plaque at Nollendorfplatz is the first sign to prominently commemorate the homosexual victims under Nazism and acknowledge the history of their persecution in a public space. Rainbow flags can be seen flying all over the streets of Berlin today, and her queer culture is known worldwide. But this small commemorative plaque on the side of the road wasn't accepted right from the start: the Berlin Wall hadn't yet come down in the 1980s, and the issue of homosexuality was still a sensitive one. It took more than a decade of social movements by the LGBT community to get the monument nailed to the roadside wall.

Slowly, I headed north. The sun was bright, and there was hardly any snow left in the city. Unconsciously, I walked for a long time, trailing behind a few joggers in tracksuits until I found myself in Park am Nordbahnhof. This park was once an old train station, destroyed by war and later, after 1961, turned into a segment of the Berlin Wall. Now, it's a vast field of freely growing wild grass, with only the stretch of concrete walls spanning hundreds of meters serving as a reminder of its past. Yet, there are barely any blank spots left on the wall; it’s entirely covered by graffiti of various styles. A bearded man, hiding under a hooded sweatshirt, fiddled with his spray paint-filled bag. He turned around and saw me taking pictures of the graffiti behind him. He shot me a fierce glare and shielded his face with his hand. I sighed, gesturing to show I hadn’t captured him in the photo. He didn’t say more, turning his back to me and began painting over the graffiti behind him.

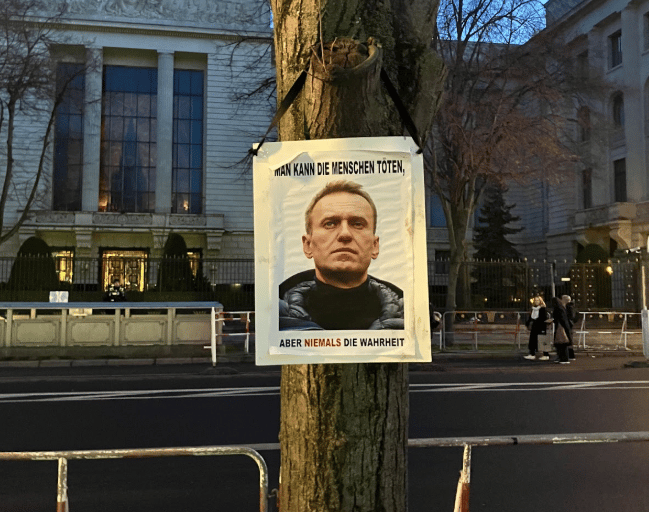

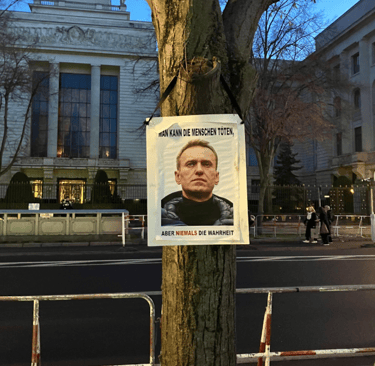

In one picture, Navalny sat confidently in a chair, offering a playful smile in a crisp dark suit. “He could have been President,” some still believed. There he was, featured in The Times, gazing back in a nostalgic portrait. His slogans. His prayers. A photo of him beside an Orthodox saint – like a holy fool. Those who didn't witness his life might struggle to understand why, for a man seemingly destined for a tragic end, many forgot he could die before that end truly came. Even now, I often feel bewildered – how could someone like him die?

More than once, he returned from death, bringing new speeches and jokes. He was an ambitious politician, a unifying street idol, a dangerous genius of opposition, a patriot, a flippant blogger, and a loyal lover. So vivid and complex, people loved him, hated him, feared him. With his toothy grin, he'd satirize those in power, quote children's cartoons in court, and recite Shakespeare in prison. He went from an awkward, somewhat conservative country boy into a more mature, open, and powerful politician, making one wonder what would happen next. For a time, he seemed to achieve the impossible. He did not.

Then he paid the ultimate price. No one has divine assistance; he too could die. A distancing way to put this: everything is just another pass in the long relay race called history. But in this vast frozen land, no great work was ever accomplished in a single bound. Nemtsov said Russia is a cruel country where no one can do something important and progressive for her without paying a price. But Nemtsov didn't leave, and neither did Navalny, who missed Nemtsov's funeral while in detention nine years ago. And so he too died in February.

I returned to Brandenburg Gate. Empty, in every sense. Only three groups remained: police officers standing under the arch, their expressions obscured by shadow; four hotel security guards, joking as they ended their shift; and a couple kissing under a streetlight, their silhouettes nearly merging into one.

What had I expected to see? Nothing is open on Sunday in Germany and I clearly forgot that. I felt foolish. The Union had won. AfD would not be part of the government. Wasn’t that enough for a peaceful – perhaps even sweet – night in Berlin? Whatever the percentage, life moves forward. The undercurrents of a windless sea may be wild, but tonight must be calm. Many could finally sleep.

Fall asleep. Have a nice dream. Have a sweet one. Forget we are on a bus. Assume we will be taken home. I told myself this, while the Flixbus rattled slightly, in sleepy silence, taking me out of Germany.

Covering someone else's graffiti isn't exactly vandalism – though the city authorities would claim graffiti itself is vandalism – it’s part of the natural cycle of graffiti landscape renewal. However, artists erasing their own work isn’t unheard of in Berlin. In December 2014, street artists Blu and Lutz toiled through an entire night, painting over their own 1,000-square- meter mural in black. Known as the Cuvry-Graffiti, these two massive paintings in Kreuzberg were considered some of Berlin’s most iconic street art, frequently featured in souvenirs and city albums. One of the graffitis depicted two figures pulling at each other’s masks, their gestures clearly representing the identities of East and West Berlin. The other graffiti, however, foreshadowed their eventual fate: a businessman wearing a gold watch that also served as handcuffs. According to Lutz’s statement, the act of erasure was meant as a protest against Berlin’s growing gentrification.

Not far from the bridge, Schlossbrücke, an oddly mismatched small parade passed by – a group of seven or eight young men riding a multi-person bicycle through a line of red lights. Accompanied by electronic music, they shouted at pedestrians while a group of young girls wearing fur hats laughed and posed for pictures nearby. A sign next to them read “DDR Museum, 200 meters.” Behind me loomed the Berlin Cathedral; its lower marble columns were nearly blackened with age as Protestant saints gazed into the distance from their lofty perches – Huldrych Zwingli entirely shrouded in darkness while his bronze cross still gleamed brightly.

Out of some instinctive desire for self-comfort, I decided to visit the DDR Museum first before returning to Berlin Cathedral. However, upon my return to the church, what filled my mind wasn’t horror at peering into historical abysses but rather an overwhelming frustration at feeling toyed with. The DDR Museum largely resembled a theme park sustained by tacky souvenir shops rather than an educational space. In an exhibition hall no larger than an underfunded university classroom, visitors crowded together; older folks appeared indifferent while two young people on a school trip busily kissed each other. A girl with thick glasses stared vacantly at an image of Honecker while several children played with replicas of East German toys.

The exhibits were not only sparse but also presented in an overly interactive format. Which further transformed East Germans' lives devoid of political freedom into a nostalgic alternative lifestyle. Everything had been simplified; forty years of East German life were casually divided into several panels with just a few lines explaining their isolation and suffering – how they suddenly found courage from who knows where. “Aha! Kids, see? This is how East Germans were deceived by communists and Russians,” was the impression this so-called DDR Museum left me with.

Still burdened by disappointment, I stepped into the Berlin Cathedral. Beneath the towering dome, the deliberate hush washed away my indignation. The sense of history, to me, only reveals itself in silence. So we make one foolish choice after another in our noisy cities, convinced we’ve transcended the continuum of time. But we haven’t. We’re just loud. And if I enter a church while traveling, it’s usually to catch up on sleep, if not or after admiring anything. Why not? God’s happy. In front of me, a young man had dozed off in his girlfriend’s arms. To my right, an elderly gentleman wandered in and immediately drifted to sleep. Above the altar, a plaque embraced by angels read, “Let’s Reconcile with God.” So I took the old man’s lead, let my body sink into the pew, and closed my eyes.

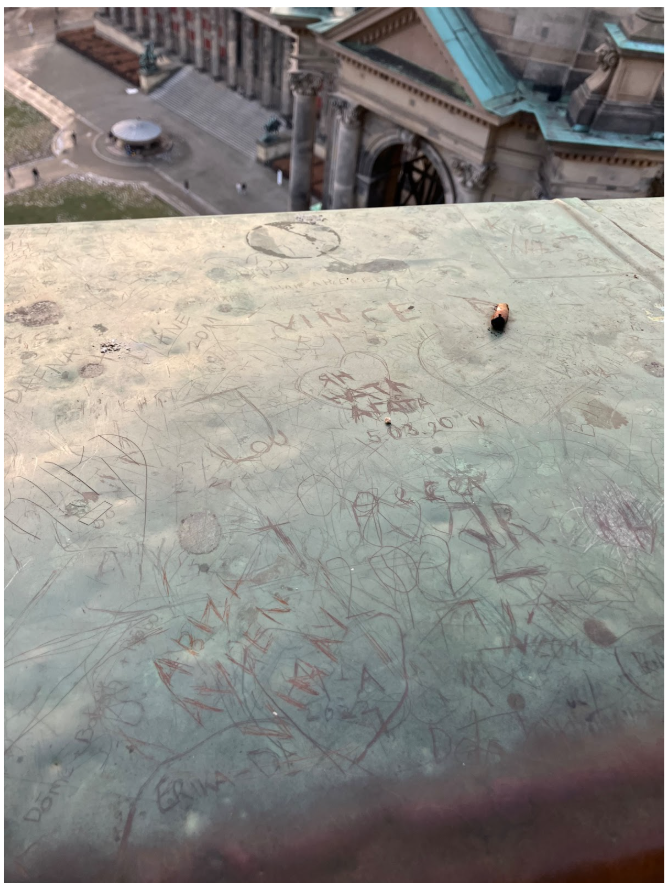

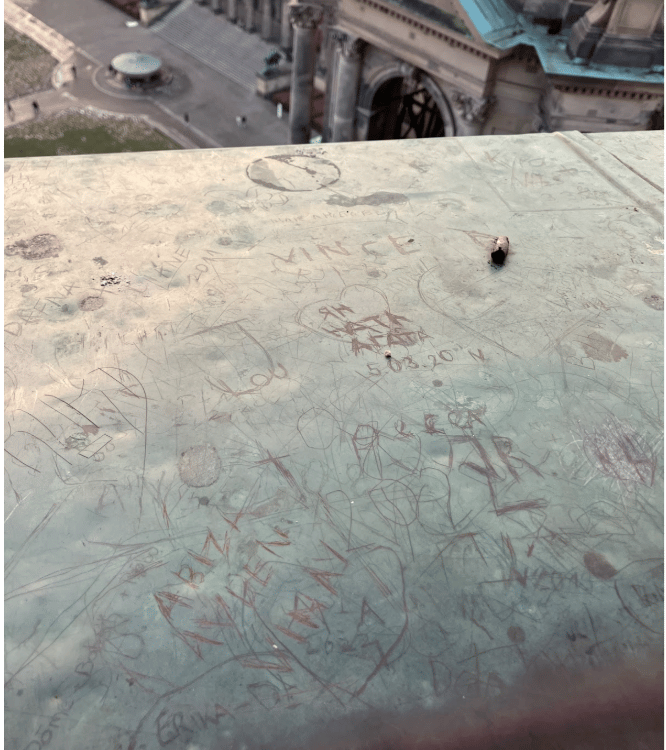

An hour or so later, I woke refreshed. I walked past the sarcophagus of King Friedrich I and Queen Sophie Charlotte, the first crowned rulers of the Kingdom of Prussia, ushered into bloodier European strife in 1701 from Königsberg. I entered a narrow rear passageway, climbing step after step through faded red masonry, time-worn and even a bit of crumbling. Yet I felt no oppression – just the cool breeze threading through my collar, breathing clarity into my lungs. At the top, I stood behind the martyrs and pioneers of Protestantism, leaning against a copper railing scarred with handwriting and scratches, a myriad of old loves and former rebellions crowded into this ghostly green copper.

I looked out. The Altes Museum, dedicated to the gods, stared back at the one true God beneath my feet – a mutual gaze stretching over a century. On the Schlossbrücke Bridge, eight white marble statues of Athena, Nike, and Iris. Across the bridge, the Foreign Ministry building rose with its NS-style glass facade – concrete with the weight of power, guarded by armed police. (Interestingly, the AfD billboard near the foreign ministry was the only AfD billboard that hasn't been defaced, with Ms. Weidel displaying a clean, confident smile.) In the distance is the Berlin TV Tower, cold and tall, a communist structure that looked down on all life from above. And further is the Park Inn Radisson Hotel, an East German icon, renovated at the dawn of the new millennium, completely covered in glass, tightly pieced, and glittering with the capitalist triumph.

I stepped out of the cathedral, and the sun was going down, breezy. Berlin seemed a bit empty, even with enough visitors to spot, even on a chilling afternoon. Her main avenues were wide, exceptionally wide. This wideness can be traced back to imperial pride. Same as in Paris or Vienna. The designers knew, more was yet to come, marches would be carried on, museums would be built upon. After Berlin was bombed over by the Allies, the city lay buried under rubble and concrete debris; nearly everything needed rebuilding. Yet amidst all this destruction, something new rose up. As always. We are little resilient creatures.

Now it's exactly 2 PM, 22nd of February, another day; sunlight beams straight down onto my eyebrows as pedestrians move quietly forward, dragging shadows over a meter long behind them. Outside the Holocaust Memorial, nearby concrete blocks rise from a protruding foundation before descending in an unpredictable slope toward an unseen depth at their center. In the distance under shadows cast by rows of interlocking concrete blocks grinding against each other, I catch sight of an unassuming patch of white, the last bit of snow I see in Berlin. All this, however, was behind a light cordon tape, the ends of which were entangled in two fences, and trembled quietly in the breeze. A police car was parked across the street. Two armed police were chatting on the patrol, and people kept on walking.

Yesterday, a Spanish tourist was stabbed among the concrete pillars. Survived, after an emergent surgery. This should have never happened to him, also in the sense that he is just Spanish. The police said the attacker had planned to kill jews. The attacker, arrested near the scene, was found nothing with him, besides a Quran, a prayer mat, and a knife. This 19-year-old young man was identified as a Syrian, who came to Germany two years ago. He was a minor when he was granted asylum. The police said his decision was connected to the recent tension in the Middle East.

It is not even new anymore. No, it is not even new anymore. Yet, what I can never forget, and even still find chilling, is the assassination of the Russian ambassador to Türkiye, in 2016. It was not long after Russian jets bombed Aleppo, marking a deeper and more bloody involvement in the Syrian Civil War. Andrei Karlov, the ambassador, was about to give a speech at a photography exhibition, “Russia through Turks’ eyes”. That was when Mevlüt Mert Altıntaş, an off-duty Turkish police officer, fired several fatal shots from the back. Altıntaş was killed on the spot, and later Karlov died in a hospital. Many said, Altıntaş was calm, decisive and even “his move was clean”.

I simply cannot forget, when the assassin shouted, “Allahu Akbar! Don’t forget Aleppo, don't forget Syria,” this man could be a martyr or could be a devil, but he sounded almost like an oracle, with the later line: “We will not have peace, you will not have peace.”

It applies to everyone in the world at this age.

Brody L.

From reunification until the first decade of the new millennium, Berlin was undoubtedly the contemporary art capital, attracting waves of dead-poor artists from all over the world thanks to its low living costs and tolerant, inclusive atmosphere. Yet, in recent years, skyrocketing property prices have been gradually driving out artists and students. Ironically, street art has only fueled this process in ways its creators never anticipated.

The main turning point was Berlin’s city marketing campaign “Be Berlin” from 2008 to 2012. Funded by the parliament and the business sector, with support from various public and private organizations, this campaign spread visual and textual content across media platforms to paint Berlin as a livable, innovative city. While it was a well-crafted campaign, there’s no denying that the underground art of street painting quietly became a tool for promoting the city’s brand. Nowadays, when you open the “Be Berlin” website, the first thing you see is promotional ads about graffiti. On the one hand, graffiti contributes to the city’s charm, attracting tourists. On the other hand, real estate developers pour money into buying land with famous graffiti, building sexy neighborhoods for the wealthy, and consequently raising rents throughout entire areas. This pressure has become intolerable for artists like Blu, who eventually decided to refuse to be accomplices to capitalistic exploitation. So get back to the question, is Berlin still poor but sexy? I don’t know and I don’t get to judge, but being expensive is certainly not that sexy.

While some artists are destroying their masterpieces in protest, graffiti itself, once a rebellious art form, is gradually being embraced by the mainstream. With the opening of Berlin’s first graffiti museum, URBAN NATION, in 2013, street art officially took a significant step towards institutionalization. However, when graffiti is transferred from walls to canvases, when the act of painting moves from filthy, cramped streets to clean, spacious studios, can it still be called graffiti? As Banksy, the world’s most famous graffiti artist, once said: 'If graffiti changed anything, it would be illegal.”

My phone buzzed, only to be swallowed by the darkness, leaving no trace of an echo. It was 18:30 – thirty minutes after the polls had closed. When the exit poll notification came through, I was standing alone inside the Holocaust Memorial. The tapes were taken off and it was open again. Leaning against one of the concrete slabs, I heard nothing. I couldn’t even say if I saw anything. It was one of 2,700 slabs, each slightly different in height, yet I had chosen this one. They all shared the same pale grey, cast under the same muted light. Doubt lingered in the chilling air. It was simply too quiet.

Stepping out of the translucent mist, I felt the air begin to move again. Even with a few cars passing through, Hannah Arendt Street remained eerily silent. Brandenburg Tor stood empty. Tonight, Berlin floated on a windless sea.

When a moment is recorded without a scene made, where do we find the news? So I zoomed in a bit. At 17:40, not many walked alone past Brandenburg Gate. With no crowd blocking the view, Navalny could have clearly seen the quadriga atop the gate. His photographs were scattered across different angles – at the Freedom Square, along the boulevard of Unter den Linden. When I passed by, an old man sat grumbling in Ukrainian on a nearby bench. People came and went along the snow-melted dirt track, occasionally pausing to take a closer look.